Lead Author: Pauline Londeix

Organization: ACCESS

Country: France

Abstract

INITIAL FINDING

Current treatments for the hepatitis C virus (HCV) would result in the eradication of HCV. Although the pandemic is now on the upswing, political will could reverse it. In early 2014, Médecins du Monde [Doctors of the World] published a report analyzing the pharmaceutical industry’s traditional strategies and comparing them to specific HCV epidemiological data. Whether they involved “standardized” pricing in high-income countries (HIC), “differentiated” pricing in middle-income countries (MIC), or voluntary licensing in low-income countries (LIC), this report demonstrated that access to these new medicines is being compromised.

RESULTS

Two years after this publication, it is clear that the pharmaceutical firms’ commercial strategies block access. These profit-based strategies are not compatible with the goals of universal access. What is more, these commercial strategies are to the detriment of respect for basic human rights, insofar as countries, including those with strong political wills, are unable to guarantee universal access to medicines because of their costs. In terms of public health, this is an aberration, to the extent that it is sometimes expected that patients must progress to a more advanced stage of fibrosis to obtain access to DAA.

CONCLUSION/ RECOMMENDATIONS/ IMPLEMENTATION

Recourse to flexibility in TRIPS [trade-related intellectual property] agreements is often found to be effective in terms of access. But this must be encouraged and supported by international institutions despite political pressures. These institutions must ensure that a generics industry and strong and independent sources of raw materials are capable of supplying countries that are excluded from voluntary licenses. Furthermore, at the same time, research and development systems and the negotiation of medicine prices must be completely re-thought and re-organized in order to conform solely to public health challenges, with no profit logic whatsoever.

Submission

The WHO [World Health Organization] estimates that 150 million people around the world are infected with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV). The HCV epidemic is concentrated in middle-income countries (MIC), which account for 72% of affected persons, followed by 15% in high-income countries (HIC) and 13% in low-income countries (LIC) [i1]. 2014 marked a major turning point in the history of the HCV pandemic. New “direct-acting antiviral” (DAA) [1] treatments, which arrived on the market in early 2014, present a number of advantages over their predecessors (Peginterferon and Ribavirine).

The arrival of DAAs is the culmination of immense hope for millions of people who carry HCV, as their use may result in excellent treatment success rates. The most important molecule is sofosbuvir, which is marketed by Gilead, and is considered the “backbone” of the new cures. Declastavir, sold by Bristol-Meyers Squibb, is a priori the best option in combination with sofosbuvir.

“We are witnessing a revolution in the treatment of hepatitis C virus, with powerful molecules capable of healing the infection. There is no question that these treatments, which can save millions of lives, are not universally available at an affordable price,” declared Nobel Medicine Winner Prof. Françoise Barré-Sinoussi, on the occasion of the publication of the Médecins du Monde report “New Hepatitis C Treatments: Strategies for Universal Access.” [2]

This study heralded the arrival of the new treatments but showed concern at the issue of access. The study sought to determine whether universal access to these new treatments would be a reality in HIC, MIC and LIC. To this end, the report examined marketing strategies implemented by the brand pharmaceutical industry in all the various World Bank country categories with regard to access to HIV/AIDS treatments, and tried to estimate the number of persons affected, applying epidemiological data specific to HCV.

“Although they resulted in improved quality of life for individuals infected by HCV and an increased number of healings, the price of these new molecules put them out of reach of most people who needed them.” Médecins du Monde found that if these marketing strategies involving standard pricing, differentiated pricing and recourse to voluntary licensing were applied to the new HCV medicines, access to the medicines by the largest number of people would be impossible, particularly in countries (the majority) that lack national programs or a sufficient budget to combat hepatitis.

To guarantee a better impact in terms of public health, better consistency in the global HCV response and compliance with the basic human right of access to health, Médecins du Monde recommends learning from the lessons of the struggle against HIV/AIDS. “Although none of these strategies

favor access, what are our other options? In the case of HIV/AIDS, recourse to flexibility in TRIPS agreements has yielded very good results in terms of access and reduced prices of medicines.”

ACCESS TO HCV TREATMENT IN MIDDLE-INCOME COUNTRIES

The MdM [Médecins du Monde] study thus studied the pharmaceutical industry’s various commercial strategies around the world, as a function of the categories established by the World Bank. The five countries where the largest number of persons infected by HCV are concentrated are China, India, Egypt, Indonesia and Pakistan. According to the World Bank’s criteria, these countries are “middle-income countries” (MIC) [3] [4]. In MIC, the pharmaceutical industry holding active ingredients traditionally applies a “differentiated pricing” policy, which consists of proposing specific prices for each country, most often as part of opaque bilateral negotiations. A country’s negotiating abilities differ depending on its size, the likelihood it will resort to generics if its domestic laws so permit, its industry and the political will of the current government.

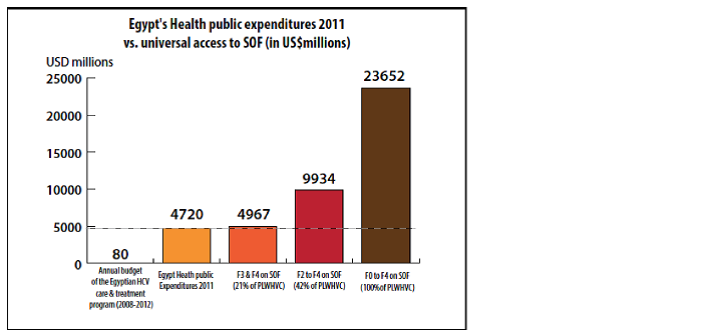

The Médecins du Monde study took the case of the cost of sofosbuvir in Egypt [i2] and Indonesia [i3]. In Egypt, the administration of sofosbuvir (alone) at the minimum price of 2,000 USD (price mentioned by Gilead at the time) to this entire population represented five times the country’s total public healthcare spending in 2011. In April 2014, the Egyptian patents office rejected Gilead’s patent application for sofosbuvir due to a “lack of innovation,” which afforded an opening to competition by generics on Egyptian territory. In order not to lose ground in the Egyptian market, Gilead finally included Egypt in its voluntary licensing program (VL) [5]. Competition by generics led to a low starting price of 800 USD for 12 weeks of treatment [6]. In reality, this price drop resulted from Gilead’s alignment on the price, as it was expecting to propose the Egyptian laboratory in the process of placing a generic on the market.

Médecins du Monde further emphasized that in Indonesia, over 9.9437 billion USD “would be necessary, i.e., slightly over the total annual healthcare budget, to supply sofosbuvir (alone) at a minimum price of 2,000 USD to 50% of the 9 million individuals living with chronic HCV.” Even if Gilead’s price in Indonesia was not yet confirmed, this projection had the advantage of applying a kind of order to the inconsistency and lack of reality of the policies implemented by the pharmaceutical industry in their treatment access programs, and the firms’ lack of interest in the impact of their programs on public health and healthcare systems.

A study was carried out by the organization I-MAK, which estimated the over-pricing due to lack of recourse to generics in several MIC [7]. These figures tell an eloquent story, and clearly demonstrate the consequences to healthcare systems of the lack of competition by generics.

These prices also prove that pharmaceutical firms do not seek to guarantee access to all their medicines, but are essentially aimed at also generating the greatest possible profit as quickly as possible. It might appear legitimate for richer countries to pay more than poorer countries for a given medicine. Unfortunately, in most of these countries, the constitution or the healthcare system do not guarantee free access to the essential medicines listed by the WHO.

Moreover, studies [8] have shown that the category of countries with the greatest amount of inequality, including in access to healthcare, and where most of the poor are concentrated around the world, are MIC.

Thus, even with a strong political will, most governments cannot buy new DAA at these prices, to be administered to all those who need them. That would mean dedicating a country’s entire public spending for a year or more to purchasing sofosbuvir. This would represent a major inconsistency in terms of public health. Even a strong political will and country commitments, as in Thailand and Georgia, have not resulted in a guarantee of universal access to date.

ACCESS TO HCV TREATMENT IN HIGH-INCOME COUNTRIES

In the United States, Gilead set the price for sofosbuvir at 1,000 USD per capsule, i.e., 84,000 USD for 12 weeks, which does not include the cost of other necessary molecules, diagnosis and biological monitoring. In this country, where the health insurance system is very complex and reimbursement systems vary, one portion of the individuals who need treatment must pay a share of this amount out of pocket [9] [10], as the various insurance systems have not truly tried to negotiate the best prices with firms. In the United States, sofosbuvir alone administered for 12 weeks costs 1.5 times more than annual average household income [i4]. The pharmaceutical lobby’s influence on politics and domestic economics prevents any transparency in the process surrounding medicine prices. However, recent studies have shown that generics, which represent some 80% of the medicines administered, “helped Americans save 193 billion USD in 2011” [11.]

In France, where the health insurance system allows patients to avoid these costs, Gilead initially requested over 61,216 USD from the Health Ministry for sofosbuvir. In 2014, individuals affected by fibrosis stages F2 to F4 and those suffering from complications represented 55% of the 232,196 persons affected by chronic hepatitis in France, i.e., 127,700 persons for whom treatment should be initiated [12]. The cost of sofosbuvir to the health insurance regime would therefore be 9.92 billion USD, which for comparison purposes, represents four times what France has paid to the Global Fund Against AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (GFATM) since 2001 [I5].

In France, Gilead set its price at 49,000 USD for 12 weeks through the healthcare authorities. The French Health Ministry then took a heavy line to the laboratory, accusing it of pricing that “threatened the equilibrium of the French health insurance system” [13]. Negotiations lasted several months until the Minister announced to the National Assembly in November 2014 that it had come to an agreement with Gilead at 44,800 USD, congratulating herself “on these negotiations, which guaranteed access to high-quality and innovative healthcare, at the best cost for Social Security and patients” [i6 and i7]. The Minister then buried the possibility of issuing an official license for sofosbuvir: “Resorting at the outset to official licensing would undoubtedly lead us to a difficult forced relationship with the laboratory,” she declared. [15] According to estimates from a study yet to be published (Londeix P., ACCESS, 2016), the combination of sofosbuvir and daclatasvir would cost 74,300 USD per person. For 55% of individuals affected by chronic HCV, and given the need for immediate treatment, it would be necessary to spend 9.492 billion USD, i.e., more than the Paris public hospital system budget [i8] and [16].

In yielding to Gilead’s demands, the French Health Ministry weakened the basic health insurance principles decreed in 1945 just after the Second World War, including fairness and non-discrimination in access to care [17]. This choice was thus made despite good sense and the possibility of the French government’s resorting to flexibility in the TRIPS, issuing an official license, importing or producing a generic.

In the United Kingdom, the National Health Service (NHS) decided not to provide reimbursement for sofosbuvir [18] due to its price. In Germany, the healthcare authorities have recommended that doctors only prescribe sofosbuvir in the absence of any other alternative treatment. In Spain, given the consumer price of sofosbuvir, the government decided that only a very small number of individuals, i.e., fewer than 2% of those needing treatment, will have access to the treatments [19].

Two years after placing DAAs on the market in Western Europe and the United States, the MdM report accurately foresaw that the “standardized” pricing of Gilead and BMS would restrict access to DAA or considerably burden the healthcare systems, to the detriment of the combat against other diseases or the financing of other programs, which is an aberration in terms of public health, consistency in the policies carried out, and access to the basic human right of non-discrimination in access to care.

ACCESS TO HCV TREATMENT IN LOW-INCOME COUNTRIES

The signing of voluntary licenses (VL) is the strategy most often employed by the pharmaceutical industry in low-income countries (LIC). VLs address the firms’ industrial interests, allowing them to continue controlling markets. Unlike mandatory licenses, VLs are not based on flexibility in TRIPS. In the case of access to new HCV treatments, are VL effective? This question, which was raised by MdM in its report, found the start of a response over a two-year process. In 2014, Gilead approved a VL for sofosbuvir to Indian firms that produce generics. The first VL covered 60 countries. Later, this geographic territory was extended [20]. In

November 2015, BMS announced a VL agreement for daclasavir with the Medicines Patent Pool (MPP) [21].

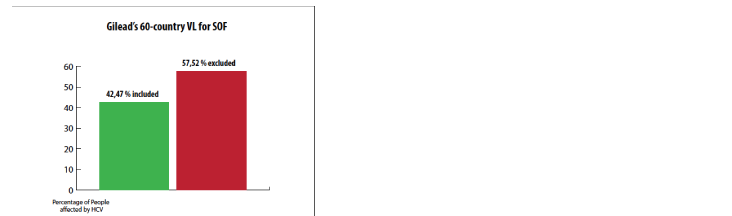

VL on new HCV treatments have confirmed MdM’s hypothesis [i9]. In September 2014, HepCoalition.org performed new calculations, taking into consideration the new countries included in the geographic territory of the Gilead VL. 73 million individuals were potentially excluded from access to sofosbuvir [22]. A number of MIC, including China and Brazil, were excluded from this license.

Since 2014, have persons infected by HCV in countries included in these VL had access to the medicines? The minimum price for 12 weeks of sofosbuvir in generic form sold through the Gilead VL by an Indian generics producer currently remains exorbitant for LIC (800/900 USD/ person/ 12 weeks). A country such as the Democratic Republic of Congo, where millions of people are living with HCV, is characterized by a lack of basic healthcare structure, and has only very few chances of offering sofosbuvir to its population in the future at anywhere near 900 USD per person. In conclusion, in the absence of GFATM that allow for financing of the purchase of HCV treatments, it is quite likely that a number of people in LIC will suffer a lack of access to sofosbuvir. The contribution of these VLs is therefore only theoretical.

Moreover, by “waiving” its intellectual property rights in certain countries, Gilead and BMS have given a tainted gift to the PMA [sic; abbrev. not expanded in source] covered by the VL, insofar as the PMA have a period of time to apply the TRIPS and are not required to award patents, territorial law [sic]. In other words, in certain countries, Gilead, BMS and the MPP receive royalties for a medicine on which there is no intellectual property right.

Finally, in Egypt and Morocco, the patents offices of these two countries rejected Gilead’s patent application for sofosbuvir. In Egypt, a local laboratory began production of a generic. In Morocco, firms have stated their interest in doing so. To block development of the generic production of sofosbuvir outside India and its VL, Gilead decided to include these two countries in its VL.

Thus, it clearly appears that VLs allow the brand industry to control the production of generics, by keeping its thumb on the market for raw materials and by preventing generics producers who have signed a sub-licensing agreement from supplying countries excluded from the license, i.e., most MIC and HIC.

CONCLUSION

Unlike the situation facing HIV or HBV [hepatitis B virus], new treatments afford the hope of eradicating HCV. Although the pandemic is currently on an upswing, international and national political will would allow for a reversal of this trend, and attainment of the goal of eradication.

However, the commercial strategies of the pharmaceutical companies holding patents block access to the medicines. These policies, based on profit interests,

are not compatible with meeting the public health objectives of international organizations. What is more, these commercial strategies violate respect for basic human rights, insofar as even countries with high political will are unable to guarantee universal access to these medicines because of their costs. In terms of public health, this is an aberration, to the extent that it is expected that patients must have progressed to a more advanced stage of liver disease to obtain access to DAAs, as in the case in France.

Recourse to flexibility in the TRIPS has been shown to be effective when possible. But this must be encouraged and supported. Political pressures for countries to not use this flexibility are high. Moreover, a number of developing countries are currently negotiating bilateral trade agreements with the United States or the European Commission. These agreements tend to further strengthen the pharmaceutical industry’s monopolies. These agreements are incompatible with the goals of universal access to medicines.

Finally, the brand pharmaceutical industry has found a new opportunity to extend these monopolies. It is based on control of all global production of raw materials and quasi-total control of the generics industry around the world. Thus, without access to active ingredients for pharmaceutical products, i.e., the raw materials, production is not possible, even in the absence of intellectual property rights. In the case of HIV/AIDS, a generics industry that is independent and capable of producing very high volumes has resulted in the supply of antiretroviruses to millions of people around the world. This will also be necessary in the case of HCV.

RECOMMENDATIONS AND IMPLEMENTATION

Various strategies must be implemented simultaneously to remedy the current blockage, obtain global consistency and guarantee the best impact in terms of public health.

On the one hand we need a complete recasting of the research and development system, the negotiation of medicine prices, innovation prices, access to clinical data and the production of medicines.

Thus, in order to pragmatically and immediately address the problems of access, we recommend:

- Suspending the support of UN agencies for voluntary licenses that violate the principles of universal access to treatment and the principle of equitable access to care and thus of basic human rights

- Unfailing political and technical support by United Nations agencies to allow the largest number of countries to have recourse to flexibility in TRIPS

- Setting of a maximum price for new medicines for each country, with no possibility of appeal by the pharmaceutical firms

- Decree of laws to prevent anti-competitive practices with regard to access to medicines

- A moratorium on bilateral trade agreements that strengthen intellectual property rights

Bibliography and References

[i1] illustration 1: Table showing the distribution of persons living with HCV. Source: Londeix P., with Forette C., Médecins du Monde, March 2014; “New hepatitis C treatments: strategies for universal access”

[1] “Pipeline Report,” Treatment Action Group, Hepatitis C – new direct-acting anti-virals and the best possible combinations.

[2] Londeix P., with Forette C., Médecins du Monde, March 2014; “New hepatitis C treatments: strategies for universal access”

[3] World Bank, country classification

[4] in Londeix P., with Forette C., Médecins du Monde, March 2014; “New hepatitis C treatments: strategies for universal access”

[i2] illustration 2: Egypt sofosbuvir cost estimate – Source: Londeix P., with Forette C., Médecins du Monde, March 2014; “New hepatitis C treatments: strategies for universal access”

[i3] illustration 3: Indonesia sofosbuvir cost estimate – Source: Londeix P., with Forette C., Médecins du Monde, March 2014; “New hepatitis C treatments: strategies for universal access”

[5] Hepcoalition.org, “Gilead license for the HCV medicines sofosbuvir and ledipasvir: a fools’ market! http://www.hepcoalition.org/agir/outils-de-plaidoyer/article/licence-de-gilead-sur-les?lang=en

[7] I-MAK-, see I-MAK study, September 2014

[i4] illustration 4: United States: Average annual household income vs. 12 weeks of sofosbuvir treatment.- Source: Londeix P., with Forette C., Médecins du Monde, March 2014; “New hepatitis C treatments: strategies for universal access”

[12] in Londeix P., with Forette C., Médecins du Monde, March 2014; “New hepatitis C treatments: strategies for universal access”

[i5] illustration 5: Contribution of France to the 2001-2014 GFATM vs. cost of sofosbuvir for 55% of individuals living with chronic HCV in France – Source: Londeix P., with Forette C., Médecins du Monde, March 2014; “New hepatitis C treatments: strategies for universal access”

[13] Le Monde, September 2014, Government attacks the exorbitant cost of an innovative hepatitis C medicine http://www.lemonde.fr/financement-de-la-sante/article/2014/09/29/le-gouvernement-s-attaque-au-cout-exorbitant-d-un-medicament-innovant-contre-l-hepatite-c_4496563_1655421.html#kY03cIWGoyGtVFru.99

[i6 and i7] illustrations 6 and 7: French Health Ministry press release concerning the conclusion of negotiations on the price of sofosbuvir with Gilead Laboratories (November 2014)

[15] “The minister added that measures exist, such as official licensing, established in 1992 and applied when a laboratory requests a very high price, but that it “had never been implemented” and she assumed that fee negotiations had failed. However, “negotiations are under way. (…) Resorting to official licensing at the outset would undoubtedly lead us into a difficult forced relationship with the laboratory,” added Mrs. Tourains. Le Figaro, “Hepatitis C: ‘an emergency solution’ for Touraine” http://www.lefigaro.fr/flash-actu/2014/10/08/97001-20141008FILWWW00387-hepatite-c-une-solution-d-urgence-pour-touraine.php

[i8] Cost of sofosbuvir for 100% of persons infected by chronic HCV in France, for 55% of them, vs. annual Paris public hospital system budget, 2014. Source: Londeix P., with Forette C., Médecins du Monde, March 2014; “New hepatitis C treatments: strategies for universal access”

[16] Data updated based on actual prices for Sovaldi and Daklinza in France – London P., Access, not yet published, 2016

[17] The principles of fair and non-discriminatory health insurance in access to care http://www.ameli.fr/l-assurance-maladie/connaitre-l-assurance-maladie/missions-et-organisation/la-securite-sociale/histoire-de-l-8217-assurance-maladie.php

[19] Spain/ See article: http://www.davidhammerstein.com/article-high-priced-hepatitis-c-treatments-spark-massive-public-outcry-and-political-debate-in-spain-125376732.html

[20] see [5]

[21] “Medicines Patent Pool signs licensing agreement with Bristol-Myers Squibb to facilitate access to daclatasvir, a hepatitis C medicine”

[i9] Illustration 9: Estimate of number of persons excluded from the Gilead VL with 60 countries. Source: Londeix P., with Forette C., Médecins du Monde, March 2014; “New hepatitis C treatments: strategies for universal access”

[22] see [5] and [20]

[i1] illustration 1: Table showing the distribution of persons living with HCV. Source: Londeix P., with Forette C., Médecins du Monde, March 2014; “New hepatitis C treatments: strategies for universal access”

[i2] illustration 2: Egypt sofosbuvir cost estimate – Source: Londeix P., with Forette C., Médecins du Monde, March 2014; “New hepatitis C treatments: strategies for universal access”

[i3] illustration 3: Indonesia sofosbuvir cost estimate – Source: Londeix P., with Forette C., Médecins du Monde, March 2014; “New hepatitis C treatments: strategies for universal access”

[4] in Londeix P., with Forette C., Médecins du Monde, March 2014; “New hepatitis C treatments: strategies for universal access”

[i5] illustration 5: Contribution of France to the 2001-2014 GFATM vs. cost of sofosbuvir for 55% of individuals living with chronic HCV in France – Source: Londeix P., with Forette C., Médecins du Monde, March 2014; “New hepatitis C treatments: strategies for universal access”

[i6 and i7] illustrations 6 and 7: French Health Ministry press release concerning the conclusion of negotiations on the price of sofosbuvir with Gilead Laboratories (November 2014)

[i8] Cost of sofosbuvir for 100% of persons infected by chronic HCV in France, for 55% of them, vs. annual Paris public hospital system budget, 2014. Source: Londeix P., with Forette C., Médecins du Monde, March 2014; “New hepatitis C treatments: strategies for universal access”

[i9] Illustration 9: Estimate of number of persons excluded from the Gilead VL with 60 countries. Source: Londeix P., with Forette C., Médecins du Monde, March 2014; “New hepatitis C treatments: strategies for universal access”